Juan: The Epilogue Of A Mexican Immigrant

As Juan exhaled his last breath a nearby radio station was blaring, “They’re illegal. This is America and they are breaking our laws.”

His name was Juan. Born in a small town outside of Durango, he left his village with great hope. His cousin Pancho told him that there was work, plenty of hard work and that he would be earning “dólares”. He worked in a canning factory. Juan scraped some money together from all his relatives, got the information he needed to travel to somewhere in the southwest named Hatch and said goodbye to his family.

“Be careful with the Migra warned Pancho. They wear the green uniforms. Come straight to Hatch as soon as you cross the border. Buena Suerte.” Juan was nervous but there was resolve in his eyes. He kissed his wife goodbye and promised her he would be back, that he would never forget her. Both were crying when he got on the bus going north because both knew in their hearts that they might never see each other again. They had heard many stories about how dangerous it was to cross the border and, now, it was impossible to cross back and forth as before. It might be years before Juan could return to Saltillo to see his beloved, Maria.

Maria clutched her silver Our Lady of Guadalupe necklace. Juan gazed upon Maria’s picture as he looked back at the buildings, traffic and people he was leaving behind, perhaps forever. He was thinking about how he was going to spend those “dólares”. First, his mama needed medicines they could not afford. He was going to build a little “casita” for his mama so they could move from the “vecindad” apartment they were living in. Then he would add a cuartito for his “mujer” and his little girl. They had spoken of having more children as soon as it was possible to afford the “seguro” at the hospital.

His hopes soon became dreams as the hum of the bus lulled him to sleep, his eyes still wet from the tears he had offered up to the Guadalupana.

He felt the bus come to a stop as they pulled up to the terminal in Juárez. He got off the bus and his eyes moved methodically across the bus station looking for his cousin Pepe. He wasn’t there. He sat down and waited. He was hungry but did not want to spend the “dólares” he had accumulated because he didn’t know how much he would have to spend to get across the border. “Better wait,” he told himself and contented himself with some semillas and a Coca-Cola.

A few hours later, Juan was relieved to see Pepe walking towards him. “Hola! Juan, how was your trip?” “Fine, fine,” he replied. “How is my tia Carmela?” “Fine, gracias,” Pepe responded. Pepe walked Juan outside the station and told him that a friend would take them to a drop off point. This was a place a few miles out of the city but with few Migra around. At the drop off point, Juan waited while Pepe determined the right time to cross. There was another man already waiting there. Pepe introduced them. “This is Beto. Beto this is Juan.” They shook hands and realized that they would be traveling together.

OK. “It’s time,” Pepe said. “Follow that line and when you get to that point wait for a few minutes. The Migra will pass by in about 15 minutes. Wait for another 10 minutes and then cross over. You will have to cross a road and then a barbed wire fence. Keep the sun on the right of you and when you come to another wooden fence go toward the mountain on your left. It will take you about three hours to get to where you are going. Go straight north now. OK. “Buena suerte,” he told them.

Pepe walked away, got into his friend’s car and left them there anxious and hopeful. Juan and Beto did exactly as they were told. After two hours of walking through the desert, they were close to the end of the bottle of water each had brought along. They were alright though because their destination was only one hour more away.

The hour passed and the desert seemed barren in every direction. Their breathing was labored and heavy. They both walked at a steady pace, their heads down, looking at the shadow their body created and drenched in sweat. After six hours, they began to feel a creeping fear that they had done something wrong. Juan asked Beto, “Beto, oye didn’t he say to go straight north?” “Si.” Beto responded panting. “Was the wooden fence before going straight north for three hours or were we supposed to walk three hours and then come to the fence?” “I am not sure now,” said an increasingly nervous Beto.

“I don’t see anything and I am feeling very exhausted. Isn’t there some tree or house or arroyo anywhere that you can see?” “No.” responded Beto. “I don’t see anything. What shall we do? Shall we go back?” “I don’t know. Let’s go on for another couple of hours and if we don’t see anything, we will head back.”

Hours passed, their bodies aching, their legs cramping and their breathing labored, they now were afraid. The sounds around them became menacing threats of unknown life around them and the relentless heat beat down on them like a rolling canvas, heavy and enveloping. “I don’t see anything, let’s rest near that Gobernadora plant over there and stay the night and in the morning, we can head back.”

After a long pause, Juan said, “We are not going to make it this time, a la otra, ni modo,” Juan said softly. His heart was working overtime to keep his body going but in the pit of his stomach he began to wonder whether he would escape this situation. He always had “mala suerte”. Beto was quiet and exhausted. They slept huddled next to each other back-to-back in a defensive posture against the unknown spirits of the desert.

About 5 am, Juan asked Beto if he was ready. Beto complained about his body being numb and his legs feeling very cramped, and about his thirsty and parched lips. “I am feeling the same way, amigo.” “Ni modo amigo, aguanta y vámonos”.

They began the trek south but their pace was slow and deliberate. “We have to save our energy,” said Juan. Beto agreed and they both walked quietly straight south. As they continued their trek, Juan kept his focus on his beloved Maria back home and his “mamacita”. “¡Animo Juan!” yelled Beto. “¡Animo Beto!” Juan responded. We will make it”.

After six hours of walking in the suffocating heat, Juan felt his right leg cramp and vomited. “Beto, compadrito, I can’t continue. Ni modo. Sígale and when you get back send someone for me, ¿si?” Beto looked at Juan and knew they were in trouble. “Lo siento, Juan. I will send someone, I promise you,” responded Beto as he continued with an agonizingly slow pace.

Juan sat down on the burning sand, his face burned a dark brownish red. He buried his face in his arm, breathing in the heat of the sand, feeling the burn of his skin, and the pain of his body’s muscles. He cried the few tears left in his body. He looked around and saw the cloudless sky, the bushes almost moving in the intense radiation of heat coming off the sand. He retreated into his thoughts of Maria, his mamacita and the Guadalupana. In your hands I commend myself. I am coming to visit you, Mamacita de Guadalupe.”

Juan closed his eyes and felt the pain lift from his body as a gentle peace engulfed him.

As Juan expired his last breath, the radio of the local town not far off was blaring. The speaker was on a breathless rant, occasionally sipping water, “They’re illegal. This is America and they are breaking our laws. They only come here to take jobs. Their children come on Halloween and take our candy! We should get rid of all of them. They need to be taught respect for the laws of this country.”

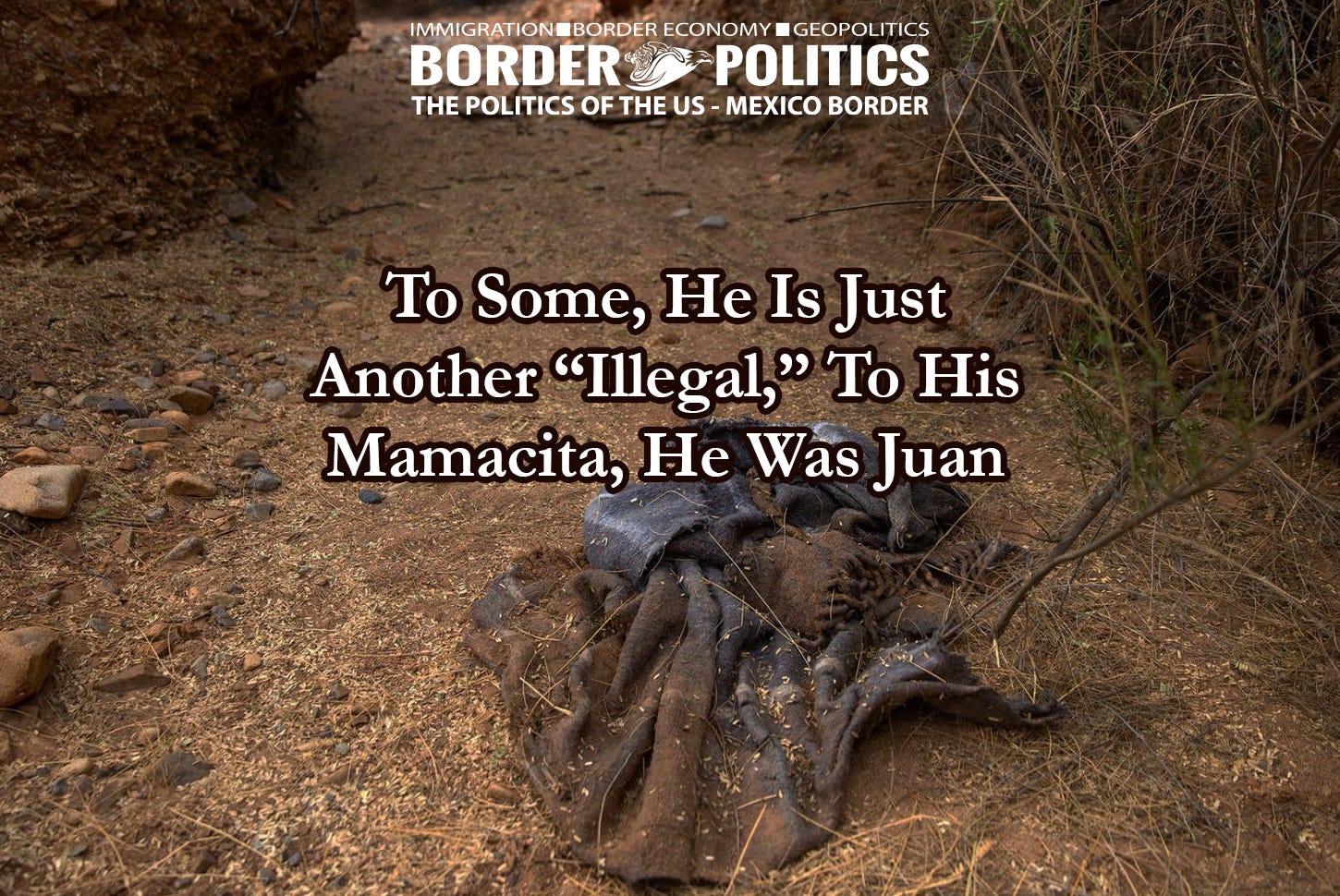

Juan lay face down, his dreams burned by the desert heat as he exhaled his last breath. But it is unlikely he learned about the any laws. He most assuredly learned the great power of the desert and a belated awareness that his life had been offered up for no purpose. He learned that his short sojourn on earth was truncated because he wanted medicines for his mamacita and a little room for his wife and his little girl.

To the most, he was just another body in the desert. To some, he was just another “illegal”. To his minacity, he was Juan.

Author’s note: The preceding is a composite of interviews by the author of immigrants along the U.S.-México border between 2000 and 2004.